But Crowther and his colleagues also wanted to figure out how much carbon-sucking potential we’ve lost due to deforestation and how much we could get back by allowing forests spring back up — and planting them — in the places they once were.

There is a distinction here between restoration, also known as reforestation, and afforestation. The latter refers to planting new trees where there were none before. The former refers to bringing trees back to areas that were previously forested, whether that’s through planting trees or allowing the woodlands to regrow on their own.

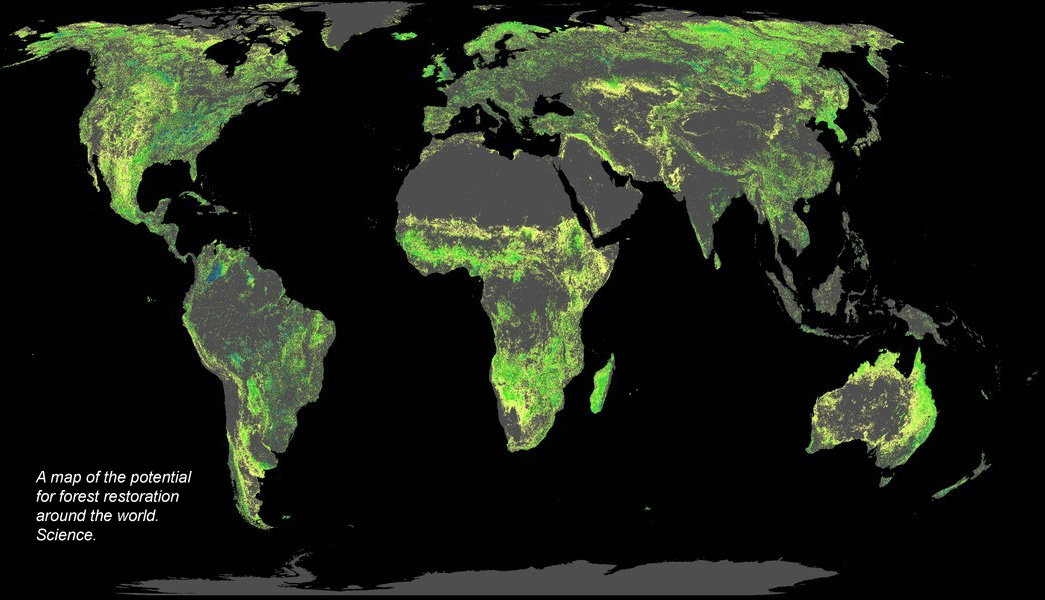

Crowther and his colleagues used global satellite images to assess tree canopies, figuring out where forests are and where they could re-emerge. They found that there are 2.2 billion acres, or 0.9 billion hectares, worth of forest restoration potential. That’s an area almost as big as the United States. Crowther hinted at these findings earlier this year and noted that this would amount to growing 1.2 trillion new trees across the planet.

From there, the scientists calculated the carbon removal potential of the newly restored forests. They concluded that the new forested areas would soak up an astounding two-thirds of humanity’s emissions in the atmosphere since the 19th century.

Robin Chazdon, a forest ecologist and an emeritus professor at the University of Connecticut, wanted to figure out which restored forests would deliver the most net benefits to humanity. Beyond mitigating climate change, trees help purify water, clean air, and provide homes to wildlife, so there’s a lot to take into account.

By Umair Irfan , Jul 5, 2019

At the same time, we’re pumping a record volume of heat-trapping carbon dioxide into the atmosphere — 2.6 million pounds per second — from myriad sources, warming the planet as a whole. While some forests may benefit from more carbon dioxide in the air, others dry out, increasing risks of wildfires. Higher temperatures can also change rainfall patterns, leaving some trees vulnerable to drought or pests like bark beetles. In other words, climate change is a mixed bag for forests.

The world’s forests have the potential to be carbon-sucking machines.

It’s important to remember that forests are not just trees. They are whole self-regulating ecosystems, from the soil bacteria that fix nitrogen to fertilize roots to the rodents and birds that spread seeds to the fungi that rot away carcasses and break down tree trunks.

All these organisms working together allow forests to push moisture into the air and pull carbon into the ground. Nonetheless, trees are a useful proxy for the work that forests do, particularly with respect to climate change.

Trees are usually 50 percent carbon by weight, and the vast majority of that comes from carbon dioxide absorbed from the air. A silver maple sapling, for example, would sequester 400 pounds of carbon dioxide over 25 years. That absorption can change based on the species of tree, its size, its age, its location, the soil it’s growing in, and the climate around it. Multiply that by the millions of trees across the world’s woodlands and you can get a sense of just how hard forests are working to keep our greenhouse gases in check.

Forests may also have other effects that can offset some of their carbon absorption. Dark leaves on trees can cause local temperatures to rise. Forests also emit aerosols, some of which have heat-trapping impacts, so reforestation does not necessarily lead to a straightforward reduction in global warming.