Restoring forests may be one of our most powerful weapons in fighting climate change.

Adding 2.2 billion acres of tree cover would capture two-thirds of man-made carbon emissions, a new study found.

By Umair Irfan , Jul 5, 2019

Allowing the earth’s forests to recover could soak up a significant amount of humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions, according to new research.

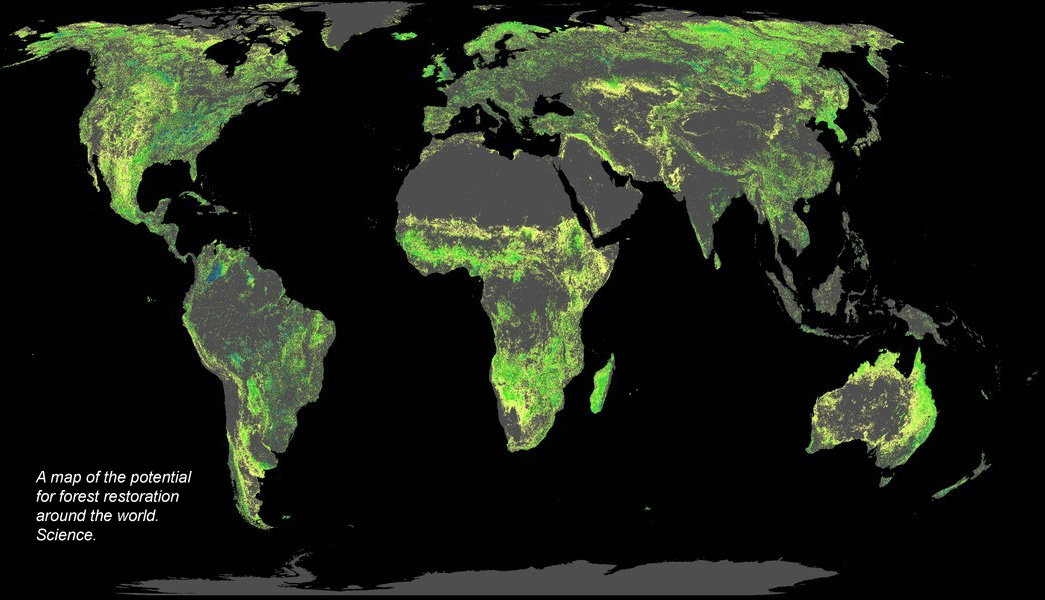

The worldwide assessment of current and potential forestation using satellite imagery appeared Thursday in the journal Science. It estimates that letting saplings regrow on land where forests have been cleared would increase global forested area by one-third and remove 205 billion metric tons of carbon from the atmosphere. That’s two-thirds of the roughly 300 billion metric tons of carbon humans have put up there since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution.

“The point is that [reforestation is] so much more vastly powerful than anyone ever expected,” said Thomas Crowther, a professor of environmental systems science at ETH Zurich and a co-author of the paper. “By far, it’s the top climate change solution in terms of carbon storage potential.”

There’s a huge potential for forest restoration, but we’re still moving in the wrong direction.

Let’s take a moment to recall why plants are so critical to the global carbon cycle.

All plants use sunlight, water, soil nutrients, and carbon dioxide to generate energy and to grow. These plants then die and decay. This returns some of the carbon back to the sky and leaves some carbon in the ground. Over time, this leads to a net reduction of carbon in the atmosphere. Plants also move moisture into the air and release aerosols that can contribute to precipitation.

So plants in general and trees in particular play important roles in regulating weather and the climate around the world. Humans have disrupted many of these patterns. Since the dawn of civilization, humans have cut down 46 percent of all trees. Just since 1990, the world has lost 1.3 million square kilometers of forested area. The situation is even more dire in the tropics, where less than half of forests remain standing today.

The modern world’s insatiable appetite for wood, land, agriculture, and mineral extraction continues to drive deforestation. In the Amazon rainforest, one soccer field-size area is clear-cut every minute.

Restoring forests may be one of our most powerful weapons in fighting climate change.

Adding 2.2 billion acres of tree cover would capture two-thirds of man-made carbon emissions, a new study found.

By Umair Irfan , Jul 5, 2019

Allowing the earth’s forests to recover could soak up a significant amount of humanity’s greenhouse gas emissions, according to new research.

The worldwide assessment of current and potential forestation using satellite imagery appeared Thursday in the journal Science. It estimates that letting saplings regrow on land where forests have been cleared would increase global forested area by one-third and remove 205 billion metric tons of carbon from the atmosphere. That’s two-thirds of the roughly 300 billion metric tons of carbon humans have put up there since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution.

“The point is that [reforestation is] so much more vastly powerful than anyone ever expected,” said Thomas Crowther, a professor of environmental systems science at ETH Zurich and a co-author of the paper. “By far, it’s the top climate change solution in terms of carbon storage potential.”

There’s a huge potential for forest restoration, but we’re still moving in the wrong direction.

Let’s take a moment to recall why plants are so critical to the global carbon cycle.

All plants use sunlight, water, soil nutrients, and carbon dioxide to generate energy and to grow. These plants then die and decay. This returns some of the carbon back to the sky and leaves some carbon in the ground. Over time, this leads to a net reduction of carbon in the atmosphere. Plants also move moisture into the air and release aerosols that can contribute to precipitation.

So plants in general and trees in particular play important roles in regulating weather and the climate around the world. Humans have disrupted many of these patterns. Since the dawn of civilization, humans have cut down 46 percent of all trees. Just since 1990, the world has lost 1.3 million square kilometers of forested area. The situation is even more dire in the tropics, where less than half of forests remain standing today.

The modern world’s insatiable appetite for wood, land, agriculture, and mineral extraction continues to drive deforestation. In the Amazon rainforest, one soccer field-size area is clear-cut every minute.

But Crowther and his colleagues also wanted to figure out how much carbon-sucking potential we’ve lost due to deforestation and how much we could get back by allowing forests spring back up — and planting them — in the places they once were.

There is a distinction here between restoration, also known as reforestation, and afforestation. The latter refers to planting new trees where there were none before. The former refers to bringing trees back to areas that were previously forested, whether that’s through planting trees or allowing the woodlands to regrow on their own.

Crowther and his colleagues used global satellite images to assess tree canopies, figuring out where forests are and where they could re-emerge. They found that there are 2.2 billion acres, or 0.9 billion hectares, worth of forest restoration potential. That’s an area almost as big as the United States. Crowther hinted at these findings earlier this year and noted that this would amount to growing 1.2 trillion new trees across the planet.

From there, the scientists calculated the carbon removal potential of the newly restored forests. They concluded that the new forested areas would soak up an astounding two-thirds of humanity’s emissions in the atmosphere since the 19th century.

Robin Chazdon, a forest ecologist and an emeritus professor at the University of Connecticut, wanted to figure out which restored forests would deliver the most net benefits to humanity. Beyond mitigating climate change, trees help purify water, clean air, and provide homes to wildlife, so there’s a lot to take into account.

By Umair Irfan , Jul 5, 2019

At the same time, we’re pumping a record volume of heat-trapping carbon dioxide into the atmosphere — 2.6 million pounds per second — from myriad sources, warming the planet as a whole. While some forests may benefit from more carbon dioxide in the air, others dry out, increasing risks of wildfires. Higher temperatures can also change rainfall patterns, leaving some trees vulnerable to drought or pests like bark beetles. In other words, climate change is a mixed bag for forests.

The world’s forests have the potential to be carbon-sucking machines.

It’s important to remember that forests are not just trees. They are whole self-regulating ecosystems, from the soil bacteria that fix nitrogen to fertilize roots to the rodents and birds that spread seeds to the fungi that rot away carcasses and break down tree trunks.

All these organisms working together allow forests to push moisture into the air and pull carbon into the ground. Nonetheless, trees are a useful proxy for the work that forests do, particularly with respect to climate change.

Trees are usually 50 percent carbon by weight, and the vast majority of that comes from carbon dioxide absorbed from the air. A silver maple sapling, for example, would sequester 400 pounds of carbon dioxide over 25 years. That absorption can change based on the species of tree, its size, its age, its location, the soil it’s growing in, and the climate around it. Multiply that by the millions of trees across the world’s woodlands and you can get a sense of just how hard forests are working to keep our greenhouse gases in check.

Forests may also have other effects that can offset some of their carbon absorption. Dark leaves on trees can cause local temperatures to rise. Forests also emit aerosols, some of which have heat-trapping impacts, so reforestation does not necessarily lead to a straightforward reduction in global warming.